By Chloe Bramwell and Lilli Steffens

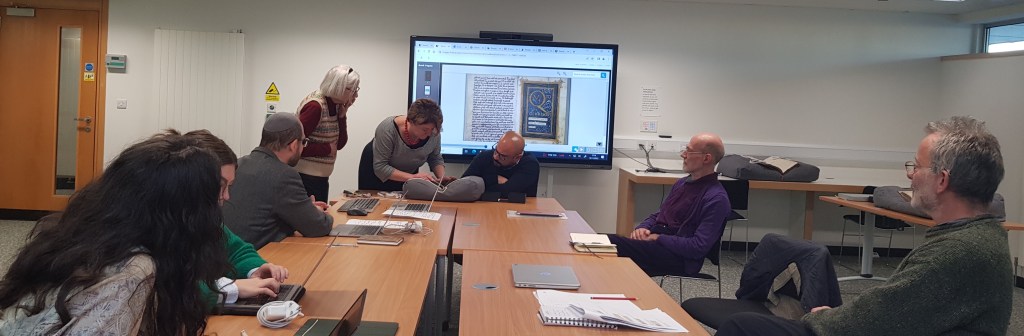

At the University of Edinburgh we are fortunate enough to have the Celtic Psalter (University of Edinburgh MS 56) within the university’s collections. It is usually dated to the 11th century, although much of its origin remains shrouded in mystery. It is frequently described as the earliest Scottish manuscript to remain in a Scottish collection. In November 2023, Prof. Heather Pulliam (University of Edinburgh) and Prof. Adam Cohen (University of Toronto) arranged a workshop at the Centre of Research Collections to bring together academics and students working in the field to attempt to learn more about the psalter, its origins, and later uses.

These included University of Edinburgh archivist Aline Brodin; Dr Beth Duncan, whose PhD thesis surveyed paleography in manuscripts from 1000-1200CE including the Celtic Psalter; Dr Carol Farr, Research Fellow at the Institute of English Studies, University of London; Dr Richard Gameson, Professor of the History of the Book at the University of Durham; Rachel Hosker, University Archivist and Research Collections Manager at the University of Edinburgh; Gilbert Márkus, Faculty Member at the Department of Celtic and Gaelic, University of Glasgow; Elizabeth Quarmby Lawrence, Rare Books Librarian at The University of Edinburgh; Jonathan Santa Maria Bouquet, Senior Conservator of the Heritage Collections of the University of Edinburgh. Two questions lay at the centre of the day: when was the codex written, and why was the decorative page for Psalm 51 (Psalm 52), ‘Why dost thou glory in malice?’ so out of place?

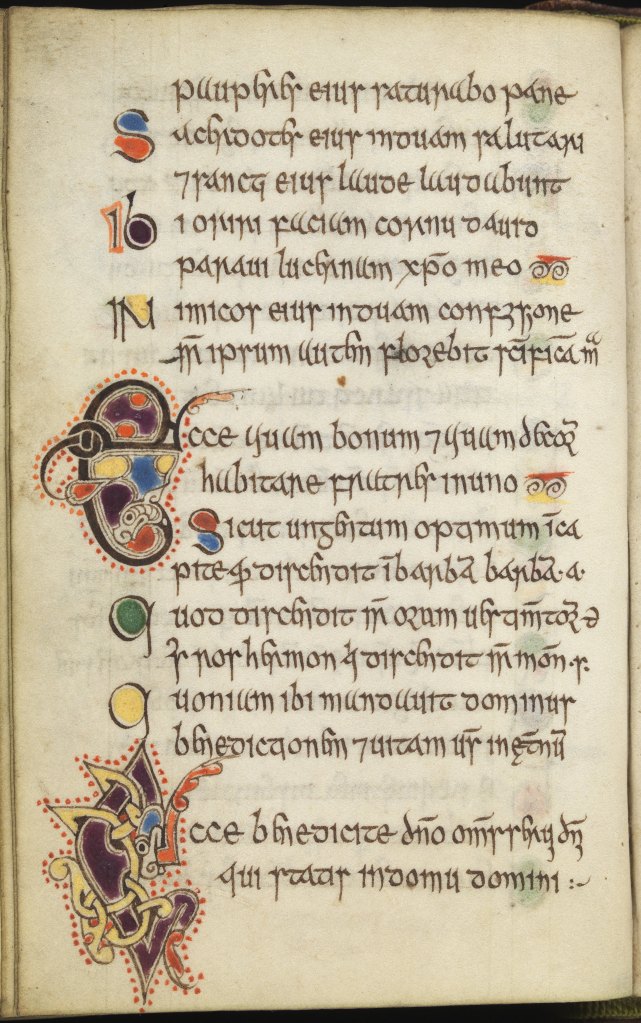

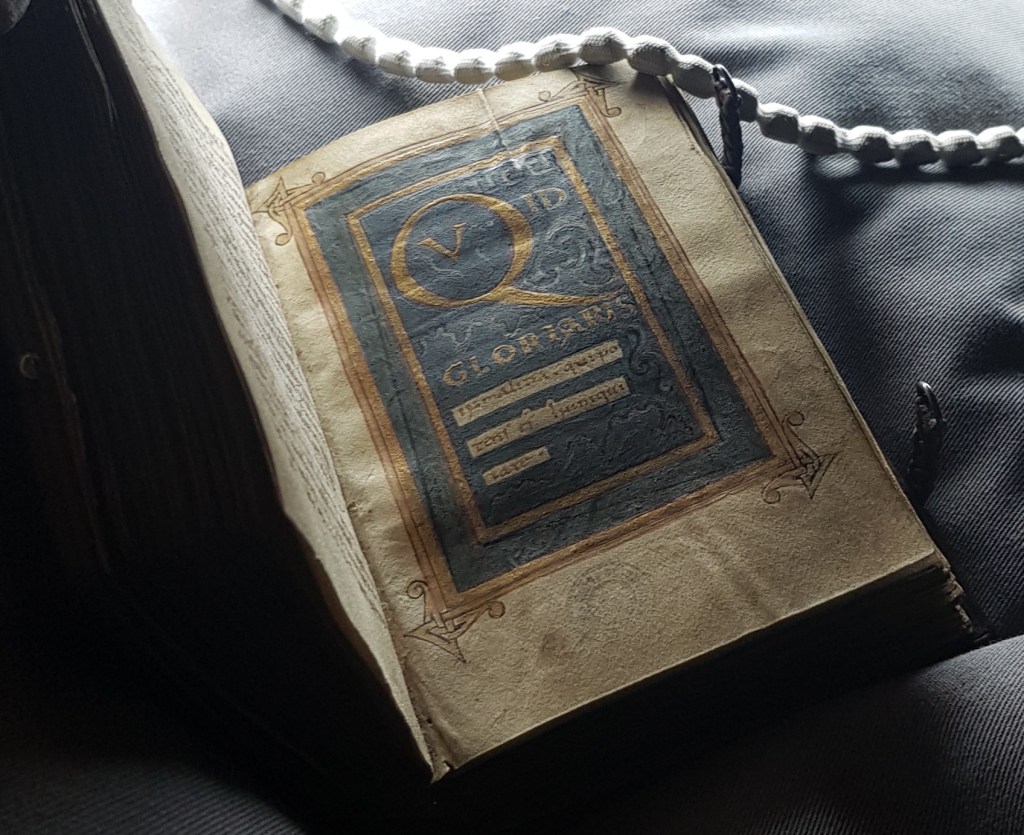

The day began with Adam Cohen, who is in Edinburgh as a Visiting Leverhume professor, giving an overview of the codicology of the psalter and in particular opening up the question of why a singleton page was introduced for Psalm 51, but not for similar decoration for Psalms 1 and 101. A recognisable feature of Insular psalters is the tendency to give decorative emphasis to Psalm 1, Psalm 51, and Psalm 101. The lively discussion which followed asked the question of whether the curiously painted page was a later addition, or if this single page was a quirk of the original codex. Looking at the construction of the book provided useful context for the creation of parchment books, and the process of their creation.

Dr Beth Duncan then presented on the manuscript’s paleography, and the sharp contrasts in the writing styles between different time and place in the Early and High Middle Ages. Using a combination of linguistic and paleographical analysis, Beth was able to place the original text as an example of late Insular minuscule somewhere in the 11th century. Later additions in Carolingian minuscule were added shortly after the manuscripts completion. As only 25 extant British manuscripts from the early 11th century remain it is difficult to say with certainty that this is when the manuscript dates from using paleography alone, however Dr Duncan was confident in saying that it was not a 12th century creation.

Moving onto pigment analysis, Dr Richard Gameson introduced us to his arsenal of non-invasive spectroscopic apparata at his disposal. Designed to be as sensitive and safe as possible to avoid damaging delicate materials, he explained how he used refraction of light to identify the various mineral and organic compounds used to create pigment throughout the Middle Ages. He then provided us with a timeline of when these pigments could be found in Britain from his work with ‘Team Pigment’ and their recent publication, The Pigments of British Medieval Illuminators: A Scientific and Cultural Study. While there are limitations in mapping British availability of pigment onto Insular manuscripts, it can at least give some indication of what is likely. Dr Duncan’s own research on contemporaneous manuscripts, such as the Coupar Angus Psalter, also helps point to fruitful answers to the many questions surrounding the Celtic Psalter.

Next, Carol Farr gave an overview of the psalter’s illumination. Probably painted by a skilled artist, the initials are impressive. With Dr Farr’s analysis as guidance, it became clear to us how many different distinctive motifs one decorated letter could contain. It was especially interesting to see how these elements could be traced back to different artistic traditions, including Celtic and Scandinavian, which are also found in other Insular manuscripts from the same period. As history students who might instinctively focus on the content of the text, seeing the illustrations of a manuscript decoded and used in determining the provenance of the psalter in this way was fascinating, and showed us an entirely new approach to the non-textual side of manuscripts.

After lunch, it was time to return to the more mystifying parts of MS 56. There is no clear evidence for when and how the manuscript came to the University library, or at what point it was rebound before the current binding from 1914. Stamps on some of the pages, as well as partially legible shelf marks on the first folio, might place the psalter’s arrival in the library between 1750 and the nineteenth century. Tracing the manuscript’s journey brought us back to look at folio 50r (Psalm 51) once more, this time under better light and with the help of Dr Santa Maria Bouquet, the conservator. Peculiarly shaded lines gave the impression that there were indentations on the page, however, under the proper lighting this turned out to be more of an illusion. The page itself, covered in dark indigo (woad) paint (as opposed to the lapis lazuli used throughout the rest of the manuscript), does not reveal much of what might be lying underneath, at least not without modern scanning technology at hand. It remains to be seen whether the indigo covered up a different design or if underneath the paint there is just a sketch for the visible artwork.

In the end, as with most historical objects we, as students, have the privilege to inspect up close and in this case even touch, they become even more real, even more tangible when their history is explored. For us, being able to witness how the different parts of MS 56 might tell us how it was made, and how it ended up in our hands, was an immense privilege. The impressions we got from only a few hours of discussion will stay with us for the rest of our academic journey, and we are grateful for these insights into the workings of historical research and for the opportunity to learn from these incredible experts. For this, we would like to thank Richard Gameson, Carol Farr, Beth Duncan, Gilbert Márkus, as well as Aline Brodin, Elizabeth Quarmby Lawrence, Rachel Hosker and Jonathan Santa Maria Bouquet from the Special Collections, and of course Adam Cohen and Heather Pulliam for allowing us to be part of this workshop and this project. We are excited to see what else the Celtic Psalter might reveal to us in the future, and what answers may be found to the questions raised in the workshop.