I am an MSc student at the University of Edinburgh studying the Global Premodern Art course, with a focus on medieval and early modern Northern Europe. This June, I had the chance to travel to the Netherlands and participate in a two-day workshop hosted by the Utrecht University Library. My supervisors, Heather Pulliam and Adam Cohen, brought together a diverse group of experts in the digital humanities, working across North America and Europe, to explore digital approaches to the Utrecht Psalter, an early medieval illustrated psalter with a number of mysteries which have puzzled historians for decades: What are its models? What are the correlations between its compositional patterns and its scribal hands? And what is its relation to other early medieval illustrated psalters? Although I had taken a seminar on the Utrecht Psalter during my undergraduate degree in Toronto, and had encountered DH in my graduate coursework in Edinburgh, I had never before considered how digital technologies might help us investigate these critical questions relating to iconography, layout, and the corpus of early medieval illustrated psalters.

Before we began to probe the digital realm for answers to our questions, each participant gave a brief presentation on their involvement in DH, detailing their approaches to the digital, which was at times philosophical, their perspective on the past and future of DH, as well as exciting new projects underway. We were introduced to projects such as eCodicesNL, DigitalMappa, Archetype, InnovatingKnowledge, Digital Scriptorium 2.0, the BASIRA Project, and Birgitta in England. Through these presentations, I learned about AI approaches to palaeography, ‘editorial archaeology’ (to borrow from Martin Foys), annotating and tagging images, new developments in IIIF, and the importance of open-source data and stable datasets. After having a lunch of sandwiches and salads and taking in the sights of Utrecht University’s colourful campus, we returned to discuss palaeography and the question of scribal hands. What struck me about this discussion is the sheer magnitude of data that might be involved in our psalter project. The manuscript would have to be turned from physical object to data, with specific inputs and outputs, so that we may work at these questions computationally. This necessitates a whole new way of thinking. Each element of the psalter image can be thought of as a unit, with identifiable attributes, and organized within a complete taxonomy. It was very interesting to me how much of this early stage of production is dependent on building a vocabulary for description. Spear, figure holding spear, figure. How incredible would it be to see every spear in all 166 illustrations cropped from their larger compositions, and placed side by side for comparison? What new questions might this generate?

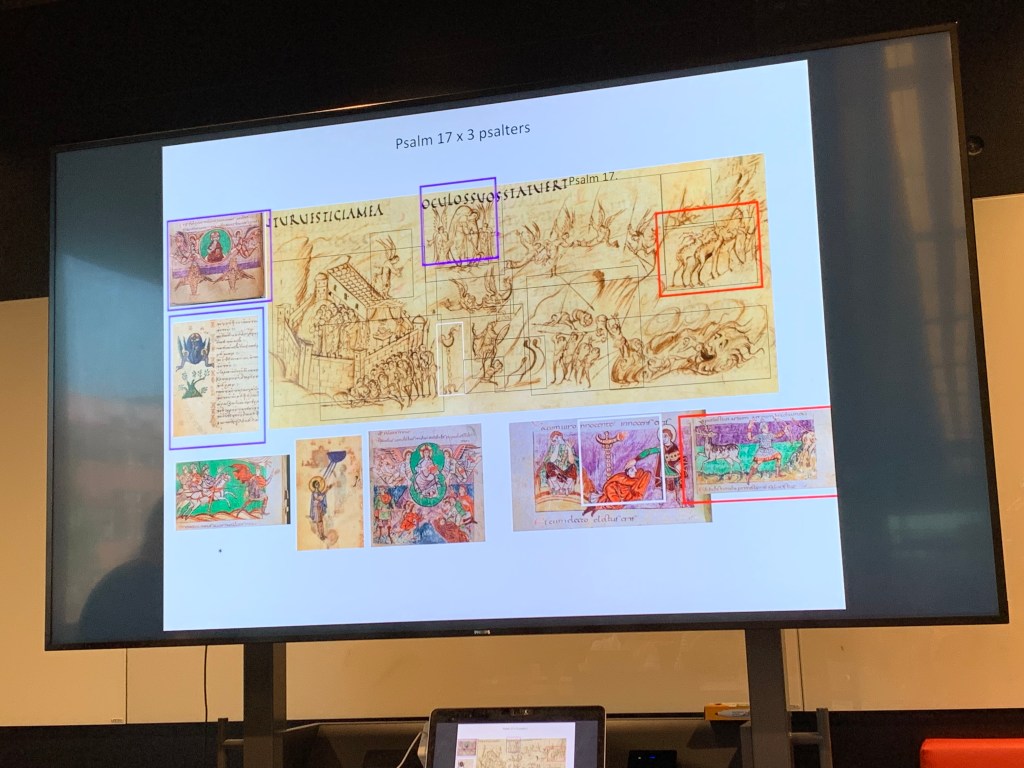

On the second day, the group discussed network analysis and how it could expand upon earlier tubular approaches to comparing the entire corpus of early medieval illustrated psalters. All of the DH experts echoed this sentiment: one needs to decide what is important, in both the research questions and the data. What can be manually described in this sea of data is limited, and the questions that we ask of this technology must be incredibly specific in order to yield results. This digital framework compels the historian to sharpen their questions and concepts until they are clear enough to be implemented. I felt that this was an important lesson to learn as a student just wading into the world of DH and beginning to understand its limits and possibilities. DH is more than just a service which increases research efficiency or access, it is an entire methodology that necessitates new questions to be asked in its language.

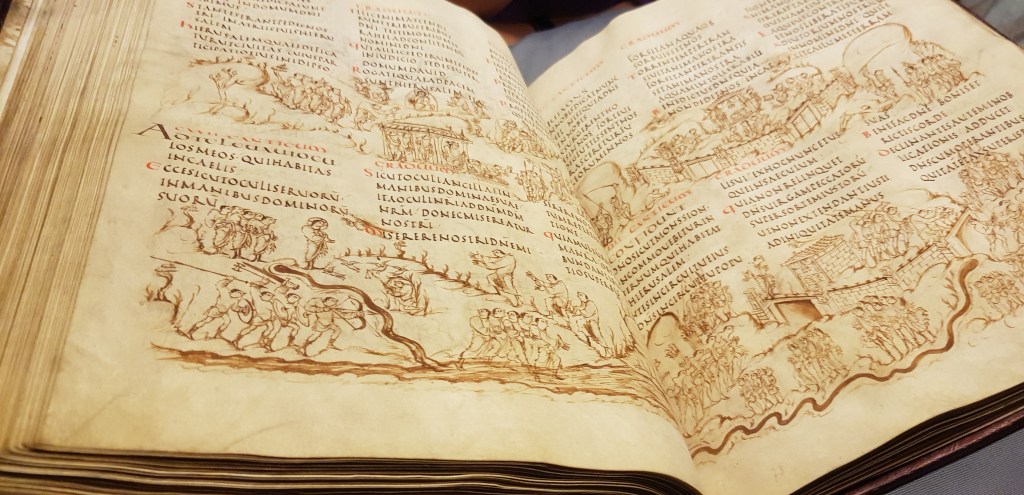

Later in the day, we had the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see the manuscript in the flesh. As Bart Jaski, keeper of manuscripts at Utrecht University, carefully flipped through its pages, I thought about how surreal it is to be in the presence of an object more than one thousand years old. He also pointed out details that usually go unnoticed in the digital version we have all become so familiar with, and we were able to appreciate the texture of the parchment, every prick on its surface, and the subtle differences in the strokes of ink from page to page. I even managed to snap a picture of fol. 88v, the canticle of Zacharias, which I wrote about in that very first seminar in Toronto—the beginning of my relationship with the Utrecht Psalter.

Over these two days, I learned so much about DH in such a short span of time. This experience was extremely meaningful to me as a student because not only was I able to be observe the beginning stages of a research project and learn about proposals, process and methodology, but I also had the incredible opportunity to learn from a number of amazing scholars in the field. Thank you to Bart Jaski, Edu Hackenitz, Martine Meuwese, Federico Rubini, Mariken Teeuwen, Stewart Brookes, Doug Emery, Martin Foys, Julia King, Evina Steinova, and of course Heather Pulliam and Adam Cohen for your staggering generosity. I am excited for the future of this project, and will be taking many of the lessons learned with me in my own future research endeavours.